Review: In ‘Takehisa Kosugi: Music Expanded,’ Violinist Uses More Than Strings and a Bow

Whitney Museuで行われた小杉武久氏とのパフォーマンスがNew York Timesで紹介されました。

By CORINNA da FONSECA-WOLLHEIM

SEPTEMBER 14, 2015

For the final piece of his performance on Sunday at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Takehisa Kosugi picked up a bow and an electric violin and proceeded to play. It was the last thing I expected him to do at that point, the end of the museum’s two-day retrospective of his work, “Takehisa Kosugi: Music Expanded.” His biography may identify him as a composer, violinist and improviser, but during the weekend’s two shows he had mostly used everyday objects: bicycle spokes, for instance, an inflatable ball, a sheet of paper, or a bag of Japanese soup mix. Some of his compositions unfolded in almost complete silence.

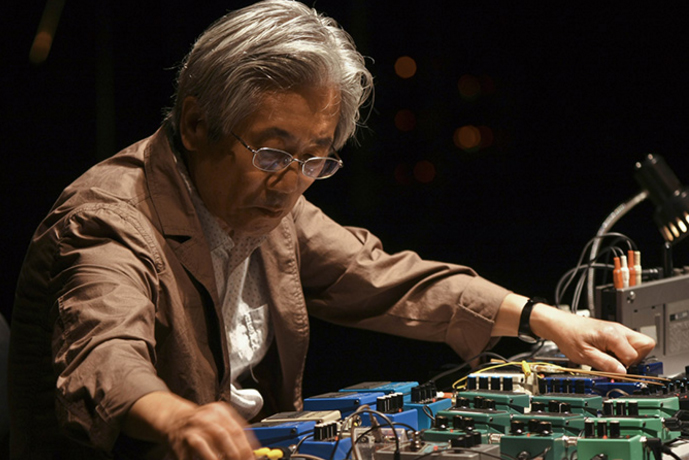

Mr. Kosugi, 77, was a leading figure in the Japanese experimental music scene in the 1960s. Part of the Fluxus movement active at that time, and influenced by the earlier nonsense art of Dada, he created improvised performances that blurred the lines between structured and random events and muddled the distinctions between deliberate sounds and those produced by biological and physical processes. He is also known for extensive electronic improvisations that make use of oscillators, synthesizers, tape recorders and flashlights, among others. At the Whitney he was joined by two collaborators, Kiyoshi Izumi and Ken Hamazaki, in a survey of works that spanned five decades and offered flashes of comedy and pathos amid long stretches of sometimes tedious, sometimes entertaining balderdash.

Many of Mr. Kosugi’s early compositions consist of a short set of verbal instructions, much like those Yoko Ono published as “Grapefruit” in 1964. That same year, George Maciunas, one of the founders of Fluxus, published Mr. Kosugi’s “Events,” a set of 18 cards detailing performance instructions, which is in the Whitney’s collection.

The simplest pieces from this collection can feel profound. For “Micro 1,” a large sheet of paper is wrapped around a live microphone and scrunched into a tight ball. For the next five minutes, the listener hears the amplified snaps and crackles of the paper trying to uncrumple itself. Five minutes was just about long enough for this sheet of paper to resign itself to its ruined state, with only the occasional despondent pop audible toward the end. I don’t mind admitting that by then I had invested considerable emotional energy in rooting for the piece of paper to spring back and was feeling a little, well, crushed.